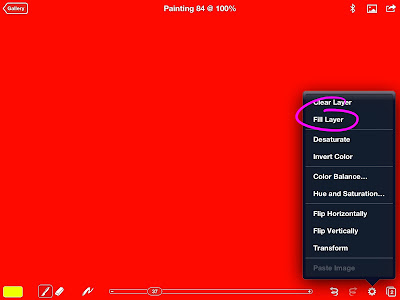

I gave this talk at TEDx Bradford On Avon last November and again, last weekend at TEDx Warminster School, with a few adjustments. I made the accompanying illustrations on the iPad using the Brushes 3 app, in real-time, as I spoke:

Let's begin at the end.

I teach people how to paint and draw.

I’ve done it for nearly twenty years now.

And lots of people seem to want to do it, but it isn't easy.

Wassily Kandinsky said that you could learn the craft of carpentry and be fairly certain of being able to make a table, but you could learn how to paint and draw and never be sure of creating a work of art.

So it can be really frustrating and you can't make any money at it. So why do it?

After a few years I began to think. All these people; If I knew why they really wanted to make art, then I might become better at teaching them how.

From the cave paintings of Lascaux to the crayon drawings of our children, the desire to make marks is fundamental. But why?

Imagine a world without birdsong.

About 230 million years ago.

230 million is such an enormous number. It’s hard to conceive what it really amounts to.

So, start counting now, take your nourishment intravenously and don’t sleep.

You’ll arrive at 230 million sometime in 2017.

230 million years ago.

No birdsong.

No birdsong because there were no birds.

So here are the dinosaurs.

10 million years go by, still no birds.

100 million years go by.

Still no birds.

A highly intelligent dinosaur wouldn't be looking up at the empty trees and thinking that a few birds would brighten up the old swamp a bit. Birds would be completely outside the dinosaur frame of reference.

So too would a giant asteroid.

Anyway, about 60 million years before a giant asteroid changes the world of the dinosaurs for good, along comes caudipteryx. Caudipteryx lived in the Cretaceous Period. Its fossilised remains were found in China, along with thirty other species of feathered dinosaur.

It was about the size of a peacock and couldn’t fly.

So the feathers were useless then.

Well, not really; they were for sex.

Display.

That’s what artists do, isn’t it? Display.

You know; pictures at an exhibition. It’s another kind of display.

Colour and movement. The sophisticated mating rituals of an advanced civilization.

You may not like the idea that the same primitive drive that put feathers on dinosaurs puts pictures on your walls, but a Damien Hirst spin painting is pretty and so too are feathers.

Birds, however, were not expected.

They just happened to happen.

Over time.

Huge amounts of it.

But dinosaurs had to happen first.

Here are some more numbers and another bird.

The billiard ball experiment is cited by Naseem Nicholas Taleb in his book The Black Swan.

The black swan is a good analogy for those things that happen that are outside our frame of reference because in the Middle Ages, the defining characteristic of a swan was that it was a large, white bird. If it was a large bird of any other colour, it couldn’t be a swan. And that was that.

Then along came a black swan and that was the end of the “all swans are white” model.

The “flat earth” model worked really well until Columbus stumbled upon America.

On a daily basis, does it matter to you if the earth is round and not flat?

I wonder, how many models do we carry around in our heads that are actually redundant, unhelpful or simply untrue?

Okay. Some more numbers.

The billiard ball experiment uses a computer model, created by the mathematician Michael Berry.

The question is this:

Can we accurately predict the movements of billiard balls on a billiard table? And if so, how far can we go?

You know. You whack the first one and off it goes, but where will it end up?

Okay. It turns out that mathematics can reliably predict the outcome of 2 impacts. That’s it.

If you want to predict as many as 9, you have to factor in the gravitational pull of anyone standing near the table.

And to compute the 56th impact, according to Berry, every single elementary particle of the universe needs to be present in your assumptions. An electron at the edge of the universe, separated from us by 10 billion light-years, must figure in the calculations, since it exerts a meaningful effect on the outcome.

And that is why billiards is a game.

How many billiard balls do we have in the auditorium today, I wonder?

All bouncing around.

So it seems that the unexpected is all around us.

And not just all around us, but in us, too.

JBS Haldane, eminent geneticist and biochemist said that after years of study, he still didn’t know why he did what he did. That it was a matter of chemistry, he thought.

And Chris Frith, Emeritus Professor in Neuropsychology at UCL said recently that actually, "We have very little access to what we're doing."

But here’s the thing:

"We think we do.”

And that’s the problem. We only think we’ve got it all worked out. We only think we know where we’re going.

And what’s on our minds.

But 90% of what the brain does is outside of our consciousness. We don’t know what it’s up to. You’re sitting on the sofa watching TV and it’s getting up to all sorts of stuff behind your back.

Like the family cat.

It's a kind of arrogance to believe that all you perceive is all that there is to the world. It's like saying that you know all there is to know.

I believe it's up to our scientists and our artists to show us otherwise.

But how?

“Fortune favours the prepared mind,” said Alexander Fleming.

Fleming was a great scientist, but a sloppy one. He left his laboratory in such a mess one weekend that when he returned on the Monday morning, he found mould growing in his petri dishes.

But Fleming didn’t bin the lot and say, "That was a waste of time." No, he studied his Mould Juice as he called it.

Later, he called it penicillin.

And in case you’re thinking that's an isolated incident:

Of the thousands of drugs on the market today. How many are used for the purpose for which they were originally developed?

Four.

Steve Jobs said, we think life is like a big, cosmic dot-to-dot drawing.

GCSE’s, A levels, a degree, a career, a pension. Do these things really tell the story of your life?

There aren’t any dots.

Out there.

Waiting for you to join them up.

A painting isn’t like a dot-to-dot drawing either. If a painter knows exactly where every dot is going to go, he or she isn’t really being creative. They’re just doing again what they’ve already done and we know that if you do as you've always done, you'll get what you've always got.

No. Being a great artist requires “giving to art what art does not have.”

Those are Francis Bacon’s words.

Give to art what art does not have. How do you do that?

Here are some more great artists:

“Make the accidental essential.” Paul Klee.

“I never lose an accident.” JMW Turner.

They’re both saying the same thing as Alexander Fleming, aren’t they?

Some more words and some numbers about JMW Turner.

Turner was painting for more than 50 years and in that time produced 24,000 watercolours.

Under those conditions, accidents will happen.

He was inviting the unexpected. And he knew, that when you invite the unexpected you must expect the uninvited. It isn’t all good. And it doesn’t always seem to make sense.

Like dinosaur feathers.

That’s why so many of the artists I know are this complex mixture of arrogance and humility. They know about the accident thing. They know that they have to be both sloppy and great and that art, like life isn’t a dot-to-dot; it’s a messy branching bush and no one knows when or where the fruit will develop; nor how it will taste.

But they work hard to make it happen.

For sex, drugs, rock’n’roll... even for art.

Music, dance, drama, poetry, literature. As Professor Mark Pagel, head of the Evolution Research Lab in Reading says in his book, Wired For Culture, this is the glue that binds our society together.

And it’s as useful as feathers on a dinosaur.

Sometimes, when look at art...

We may hear birdsong

Sometimes, when we make art...

We fly.

To see the original talk at Bradford On Avon TEDx, click here.